June 2022

Methodological Individualism and Structural Individualism

In order to understand the workings of a machine as a whole, one must look to the function of each of its parts. Similarly, in order to understand societal-level phenomena, it is not good enough to look only at macro-level structures. Max Weber argues that, “collectivities must be treated as solely the resultants and modes of organization of the particular acts of individual persons, since these alone can be treated as agents in a course of subjectively understandable action.” (Weber 1920 via Goldthorpe 2016) Although this may perhaps stand as an example of overconfidence in the power of individual action to shape collective outcome, analytical sociology recognizes the value of examining individual behaviors as a determining factor of macro-scale processes.

Analytical sociology is an approach to understanding how social facts and patterns arise through the identification of mechanisms that link individual actors to each other. Unlike purely descriptive or empirical approaches, analytical sociology focuses on identifying the underlying causal mechanisms behind social phenomena. Sociologists have not provided us with one concrete definition of a ‘mechanism’, although a helpful way to think about the role of mechanisms has been detailed by Bechtel and Richardson, who liken them to machines.

Machines are composed of individual parts. When the parts are combined, each part functions as a niche in a system in order to produce some behavior. The “mechanistic explanation” examines the parts as well as the system they are organized into, “showing how the behavior of the machine is a consequence of the parts and their organization.” (Bechtel and Richardson 1993, p.17)

Aside from its basis in identifying mechanisms, analytical sociology aims to identify the relationships that individual agents have with society at large. In this, the approach attempts to relate micro and macro-level phenomena, often underscoring the feedback mechanisms at work between these two levels of analysis (or coarse-graining for the computational sorts).

I, like those who practice analytical sociology more generally, do not argue that higher order entities such as societies or organizations are merely the sum total of their parts. Individualism is adopted as a method, but a further distinction must be made between methodological individualism more broadly and structural individualism, which emphasizes the “explanatory importance of relations and relational structures,” rather than on function alone. (Elster 1982; Hedstrom and Bearman 2009) Furthermore, structural individualism does not necessitate a dependence on rationality or intent. (for space, the argument for this will not be fleshed out here, rather see Rolfe 2009)

Crossing Levels of Analysis

As mentioned above, analytical sociology is rooted firmly in identifying the relationship between micro and macro-level processes. If we want to understand the relationship between two macro-level social phenomena (X and Y respectively in the diagram below), we must look deeper into the underlying micro-level phenomena.

One of the most famous attempts to demonstrate the interplay between cause and effect at different levels of analysis is that of James Coleman. Coleman argues that we are not able to directly observe the effect of X on Y due to feedback mechanisms at work between the individual and society. The macro factor X places a constraint on (according to Elster 1979) or affects the beliefs and opportunities of (according to Merton 1949) individual actors. This, then, affects the behaviors of individuals, which directly influence the macro factor Y.

In this, social phenomena are dynamic processes. A famous example lies in Thomas Schelling’s agent-based model of neighborhood preference. Schelling proposes that even small differences in individual preferences may have huge outcomes at the macro-level (Schelling 1978). It is only by looking at the aggregate of individual preferences that we can better understand macro-outcomes.

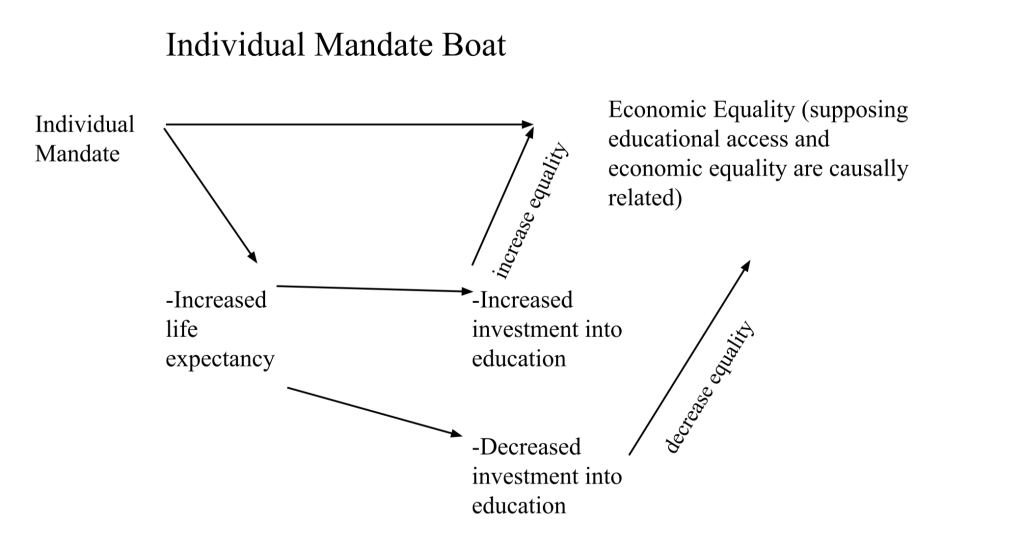

Both a strength and a drawback of this approach can also be modeled by applying Coleman’s diagram to a hypothetical social system after the intervention of imposing an individual healthcare mandate. Here, we begin to see the growing potential for confounding factors to be present in the relationship between the imposition of the mandate and socio-economic inequality in the system.

The macro change (institution of the mandate at the system-level) has a direct effect on the opportunities available to individual actors. It also changes the incentive scheme, thereby restructuring individuals’ choice preferences. After the introduction of the mandate, individuals are assumed to experience a real or expected increase in life expectancy. This information may have one of two effects. First, it may cause individuals to invest more into education, as greater chances of long-term health maintenance cause some to become more future oriented. Conversely, it may urge some to decrease their investment into education, as income previously allocated to education now will be spent on healthcare. At first, this may seem to produce a Simpson’s Paradox. However, we can continue to break down each decision pathway in order to estimate probabilities of each of these potential outcomes. With a purely empirical approach, these potential pathways would be obscured.

The Complexity Problem: Furthering the Toolset

Nevertheless, the example above also highlights weaknesses of the approach. One major drawback of sociological analysis through exploration of causal mechanisms is its ability to fail when systems become too complicated, or conversely, to oversimplify and underexplain a complex system. One may be able to think of an inconceivably large number of potential effects of a healthcare mandate on individual conditions, and these effects highlight further the potential confounding effects of factors such as class and race. The causal chain may very well be traced back ad infinitum.

In some cases, an approach using methodological individualism–which is predicated on finding rock bottom explanations for phenomena–is equally as or less useful than understanding a phenomenon through statistical analysis.

Take, for example, the increase in suicide terrorism during the period after 9/11. The use of suicide terrorism as an insurgent tactic increased across geographic locations and distinct conflicts. Many social scientists have theorized why this increase occurred and have provided explanations that include religious diffusion, changes in socioeconomic status, and interactions between Western occupiers and local populations. However, many conflicts from which an increased use of suicide terrorism sprang experienced a mix of these different influences. For example, the separatist insurgent groups the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Turkey and the Chechen Mujahideen in Russia have allowed religious influences to shape their organizations and tactics to a drastically different extent. However, the respective conflicts the groups are engaged in have endured a similar increase in the rate of suicide terrorism use as a tactic. This may leave social scientists who aim to find common underlying mechanisms of a single phenomena tangled in a web of potential causes. In this, a re-framing of the question at hand may be in order. Can some social phenomena be considered as one and the same?

The fact that sociology does not purport one grand unifying theory of social action leaves open the possibility that some phenomena are better explained at the individual level, while others may be the outcome of macro-social phenomena alone. Suppose, for example, that the increase in suicide terrorism in a geographical area is a direct function of the presence of foreign troops in an actor’s homeland (as Pape 2003 suggests). In this, it would matter less what drives individual agents to participate in suicide terrorism and more (of course an argument against this could pose terrorist organizations as the individual unit/agent at the micro level; however, suicide attacks are rare events generally perpetrated at the individual or small group level so this argument would face complications as overly thick). Along this line of reasoning, analytical sociology would provide no better insight into a phenomenon than statistical analysis.

Here, a scientist may argue that the measurement instrument should match the thing being measured. We use microscopes to look at cells and telescopes to look at the stars, not vice versa. But do analytical and empirical sociology stand as tools? Are they not higher-order frameworks that guide the creation of tools in the first place? In order for our tools to be fine-tuned to the phenomena they are listening to, they must be grounded in a solid theoretical foundation.

To some, then, analytical sociology’s greatest strength is also its greatest weakness. A dependence on structural individualism as a basis for explanation by mechanisms can create complications. It also may allow us the easiest pathway to bridge the gap between social and natural sciences. With the popularization of the computational social science discipline and the ever-growing availability of social data, we are perhaps on a path to bridging the analytical and empirical. The crossing of this bridge may well lead us to the next and even more momentous: connecting the macro and micro.

Where will a ‘grand unifying theory” of social science come from?

- We may look toward chaos theory in mathematics. Chaos theory tells us that two different, deterministic systems with very similar starting points will diverge in conditions down the line. Even if all the conditions of some social-phenomenological systems look exactly alike to begin with, down the line they will diverge and unpredictable behavior will arise. If we build a society of like individuals, behavioral pathways influenced by feedback mechanisms between the individual and society will be different between the two groups. However, the theory suggests that although we can predict not specific outcomes, we can identify a constrained set of categories of outcomes based on the underlying dynamics of the system. Two systems with similar start points will not follow the same path, but they will follow similar patterns to their diverging endpoints. Sociologists are beginning to edge toward incorporating these principles into social models (see Macy and Flache 2009), although widespread use of the mathematical language behind the theories have yet to catch on.

- Discrete and continuous systems. LLMs- Can we use LLMs to make continuous models of discrete typologies of social phenomena? If natural language reflects [is] reality (à la Wittgenstein), then lived experienced is best reflected in natural language.

- Infinite dimensional multiplex networks (see Norm Space coming soon). Thinking of layers in a multiplex network abstracted out one step further. Infinite and scaling layer spaces between which we can derive relationships via kernel methods, differential equations, etc.

- The rest of this list is under construction.